If you work on edge AI or computer vision, you’ve probably run into the same wall over and over:

- The model architecture is fine.

- The deployment hardware is (barely) ok.

- But the data is killing you—too narrow, too noisy, too expensive to expand.

That’s true whether you’re counting apples, spotting defects on a production line, tracking forklifts in a warehouse, or looking for anomalies in a security feed.

Synetic’s recent whitepaper with the University of South Carolina, “Better Than Real: Synthetic Apple Detection for Orchards,” takes a very direct swing at that data problem. In one specific domain—apple detection in orchards—they show that models trained 100% on synthetic images outperformed models trained 100% on real images by up to 34% mAP50–95 and ~22% recall, when both are evaluated on real-world imagery. SYNETIC.ai+1

So, what did they actually do, what do the results mean technically, and why should you care?

Key Takeaways

- Synthetic-first can beat real-only—even on real-world tests

In Synetic’s apple-orchard benchmark, models trained only on high-quality synthetic images outperformed models trained only on real images by up to +34% mAP50–95 and ~+22% recall, when both were evaluated on real orchard photos. Synthetic wasn’t just cheaper—it delivered better real-world performance. - The win comes from coverage, consistency, and less noise

The synthetic dataset deliberately spans lighting, viewpoints, occlusion, and rare edge cases, with perfect, consistent labels from simulation. That broader coverage and lack of annotation noise helps models generalize better than a narrow, noisy real dataset collected in one orchard (and the same logic carries over to factories, warehouses, robotics, and surveillance). - Small real datasets can hurt if you treat them as sacred

Mixing in or fine-tuning on a limited real dataset sometimes bumped a local metric, but often reduced generalization by pulling models toward that dataset’s biases and labeling quirks. For many vision systems, it’s worth treating synthetic as the training foundation and using real data primarily for validation, calibration, and sanity checks—then measuring carefully whether any real-data fine-tuning actually helps.

The Real Data Bottleneck (Whether You’re in Orchards or Factories)

Let’s start with the common pain points—because they look surprisingly similar in very different industries.

Real-world vision datasets are:

- Slow and expensive to collect.

You can only photograph what’s physically there, when the factory is running, the orchard is in season, or the vehicles are on the road. - Hard to annotate well.

Small, occluded, or rare objects are easy to miss. Ambiguous edges, partial occlusions, motion blur—labelers disagree, and you pay for that uncertainty in training. - Narrow in distribution.

One orchard. One factory. One warehouse layout. One set of cameras. You get excellent coverage of how your environment looked for a few weeks… and then your model chokes when something changes. - Biased toward “normal days.”

Edge cases—hail damage on fruit, bent parts, weird lighting, odd weather, unusual traffic—are exactly the things your model should be robust to, and also exactly the things you have very little data for.

In agriculture, these issues show up as “can’t generalize to a new orchard.” In manufacturing, they show up as “misses a rare defect type.” In logistics, it’s “doesn’t handle that weird backlight in the loading dock.”

The orchard benchmark is interesting because it’s a very controlled way to ask:

What if we stop treating that real dataset as sacred, and ask whether a carefully built synthetic dataset can actually do better?

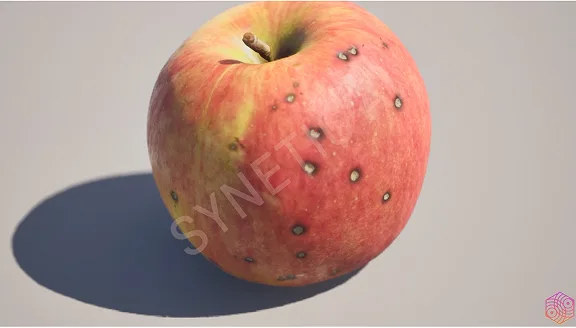

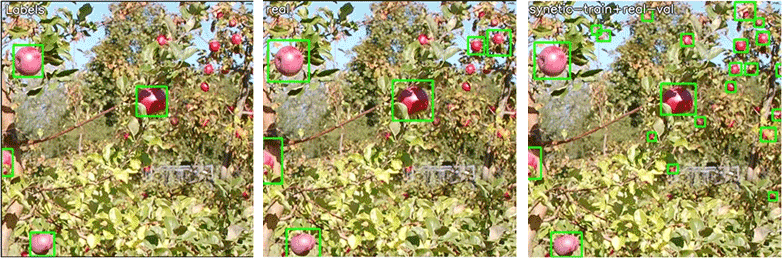

Synthetic apple imagery with fine-grained surface details, used to train and validate orchard-detection models.

The Orchard Experiment in a Nutshell

1. Two Equal-Sized Datasets: Real vs Synthetic

Synetic and the University of South Carolina set up a head-to-head:

- Real dataset

A strong public orchard dataset (BBCH81) with 2,000 hand-labeled images of apples on trees in a commercial orchard. This is the kind of dataset many teams would happily build a product around. - Synthetic dataset

2,000 images procedurally generated with Synetic’s simulation platform: 3D trees, apples, leaves, backgrounds; randomized lighting, camera angles, fruit density, and occlusion; and perfect annotations directly from the simulation.

Crucially, the datasets are matched in size, so this isn’t “we just used more data.”

Real images are used only for validation and testing, never for training in the synthetic-only regime.

2. Seven Modern Detectors

They trained seven architectures that many real teams would consider in production:

- Multiple YOLO variants: v3n, v5n, v6n, v8n, v11n, v12n

- RT-DETR-L, a transformer-based real-time detector

Training setup:

- 100 epochs

- AdamW optimizer

- Identical hyperparameters and infrastructure across all runs

The only thing that changes between conditions is: “Did you train on real images or synthetic ones?”

3. Evaluation Aligned with Edge Reality

Instead of only reporting mAP at high thresholds, they also evaluate:

- mAP50–95 – average over IoU thresholds

- Recall and precision at realistic operating points:[1]

- Confidence as low as 0.1

- IoU as low as 0.3

That’s important: in real deployments (orchard, factory, warehouse), you usually care more about “don’t miss anything important” than about pristine mAP at confidence 0.5.

The Result: Synthetic-Only Wins, Hybrid Can Actually Hurt

Across all architectures, the pattern was consistent:

- Synthetic-only training outperformed real-only training on real-world test images—sometimes modestly, sometimes dramatically.

- Up to +34.24% improvement in mAP50–95

- Up to +22% gain in recall on real data

Human “ground truth” (left) misses several apples; a real-trained model (center) still misses many; a Synetic-trained model (right) detects all fruit, including those never annotated.

In practice, that means:

- The synthetic-trained models saw more of the apples in challenging scenes

- Stayed stable at lower confidence thresholds

- And didn’t fall apart when occlusion or lighting got weird

Even more interesting: they tried hybrid setups, where you:

- Mix synthetic and real during training, or

- Fine-tune a synthetic-trained model on a smaller real dataset

You might expect that to be strictly better, however, hybrid and fine-tuned setups didn’t automatically help.

- In the joint training condition (‘Synetic + Real’), some architectures saw slightly higher mAP@50 on the BBCH81 validation set, but several also lost around 5–10% in mAP50–95 compared to pure synthetic training.

- In the separate fine-tuning benchmark that USC ran on the ApplesM5 setup, the authors report a –13.8% drop in mAP50–95 when fine-tuning a synthetic-trained model on a limited real dataset.

In other words: the small real dataset was pulling the model toward its narrow distribution and its labeling quirks, eroding some of the generality learned from synthetic data.

In this benchmark, “synthetic only” wasn’t just cheaper—it was actually better than real.

Why Did Synthetic Win? Four Lessons You Can Steal

The orchard study is very specific, but the underlying reasons are relevant whether you’re counting apples or detecting cracks in a weld.

1. Coverage Beats “Realness”

The synthetic dataset was built to deliberately cover the space of plausible scenes:

- Randomized sun position, clouds, and shadows

- Different camera heights, angles, and lens parameters

- Variation in tree structure, fruit size and color, background clutter

- Rare configurations (heavy occlusion, odd lighting) that are hard to capture often in real life

The images are photorealistic enough, but the real win is parametric coverage:

- Instead of “whatever happened in that orchard for those few days,”

- You get “deliberate sampling of many edge cases.”

Translate that to other domains:

- Manufacturing – You can systematically generate parts with scratches, dents, misalignments, and foreign objects at controlled frequencies, under varied lighting and camera setups.

- Logistics & warehouses – You can script rare but critical scenarios: dropped boxes, blocked aisles, humans in unexpected places.

- Security & defense – You can simulate a wide range of environments, weather, camera positions, and intrusion patterns that would be expensive or unsafe to stage.

The key takeaway: a slightly-less-than-perfect-looking frame that covers the right corner case is worth more than a beautiful photo you only see once.

2. Perfect Labels Beat Messy Ground Truth

In the real orchard dataset, human labelers miss apples, disagree on bounding boxes, and struggle with heavy occlusion. That’s normal; it’s also a source of silent noise in your training signal.

In the synthetic dataset:

- The renderer knows exactly where every apple is in 3D space.

- Boxes, masks, keypoints, depth—everything comes straight from simulation.[2]

- There’s no argument about whether a half-visible apple “counts” or not; that logic is encoded once, consistently.

What happens when you train on that and test against noisy human labels?

- The synthetic-trained model often “sees” objects that weren’t annotated in the real dataset.

- On paper, those look like false positives.

- In reality, many of them are correct detections of unlabeled objects.

Same story in other industries:

- In QC, labelers may miss tiny defects or disagree on severity.

- In retail, bounding boxes on crowded shelves are messy.

- In security, annotators might disagree on what constitutes a “person” versus a blob in motion.

A simulator gives you consistent, dense labels that expose the limits of your real annotations instead of being limited by them.

3. No Meaningful Domain Gap (If the Simulator is Good Enough)

One classic worry: “Sure, synthetic looks good, but won’t the model learn the wrong features?”

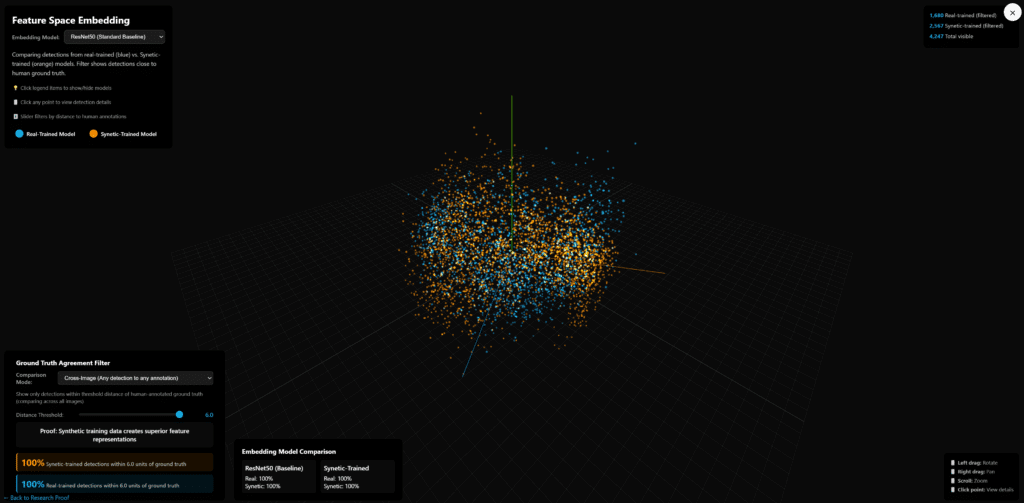

Synetic and USC dug into that by:

- Extracting feature embeddings from intermediate layers of their detectors

- Visualizing where synthetic vs real samples landed in that feature space

They found that synthetic and real samples overlapped heavily—no clean separation, no obvious “this is a different world” cluster. [3]

That doesn’t mean every simulator will fare that well. It does suggest:

- If you invest in good materials, lighting, and sensor simulation (physics-based rendering, realistic noise models, etc.),

- The model can’t “tell” synthetic and real apart at the representation level, and it doesn’t need to.

In other words, the domain gap is not a law of nature; it’s a function of how seriously you take simulation quality.

4. Beware the “Small Real Fine-Tune”

The most counterintuitive lesson: fine-tuning on a small real dataset can hurt generalization.

Intuitively:

- A well-designed synthetic dataset gives you broad coverage of the scenes you might see.

- A small real dataset is a narrow, biased sample of what you happened to see last month.

- Fine-tuning can drag the model toward that narrow sample—its lighting, camera placement, and labeling quirks—and away from the broader synthetic distribution.

The orchard experiments show exactly that: slight gains in a local metric, at the cost of worse behavior on harder thresholds and out-of-distribution tests.

If you’re running, say, a global manufacturing operation or a fleet of robots in varied environments, that’s a big warning sign:

Don’t assume “just fine-tune on a few real images” is always a free upgrade.

Sometimes you’re better off:

- Updating the synthetic pipeline to add missing edge cases, or

- Using real data primarily as a validation and calibration tool, not as the primary training set.

Synthetic-trained models aren’t limited to orchards. Here, a Synetic-powered system detects and tracks horse behavior in stalls for early health-issue detection.

Why This Matters Outside Agriculture

So why should a product manager or engineer in another vertical care about an apple benchmark?

Because the pattern matches a lot of edge/computer-vision deployments:

- Manufacturing QC

- Real data: lots of “good” parts, very few defects, heavily skewed toward normal operation of a few lines.

- Synthetic approach: model CAD, lighting, cameras, and defect modes; render thousands of rare-but-important defect examples with perfect labels and varied conditions.

- Autonomous systems & robotics

- Real data: limited to where you can safely drive or operate; collecting edge cases is dangerous or impossible.

- Synthetic approach: simulate weather, sensor noise, rare obstacles, unusual traffic, and odd geometry in a controlled sandbox.

- Security & surveillance

- Real data: dominated by hours of nothing happening, plus a handful of actual incidents.

- Synthetic approach: generate many variations of intrusions, unusual behaviors, and lighting setups across different camera placements.

Synetic themselves are positioning the orchard whitepaper as one anchor point in a multi-industry story: they explicitly call out defense, manufacturing, robotics, retail, logistics, and more as active or planned validation domains.

The claim is not “apples are special.” The claim is:

If you can build a reasonably faithful simulator of your environment and objects, synthetic data can be the default training source, with real data playing supporting roles: validation, calibration, and sanity checking.

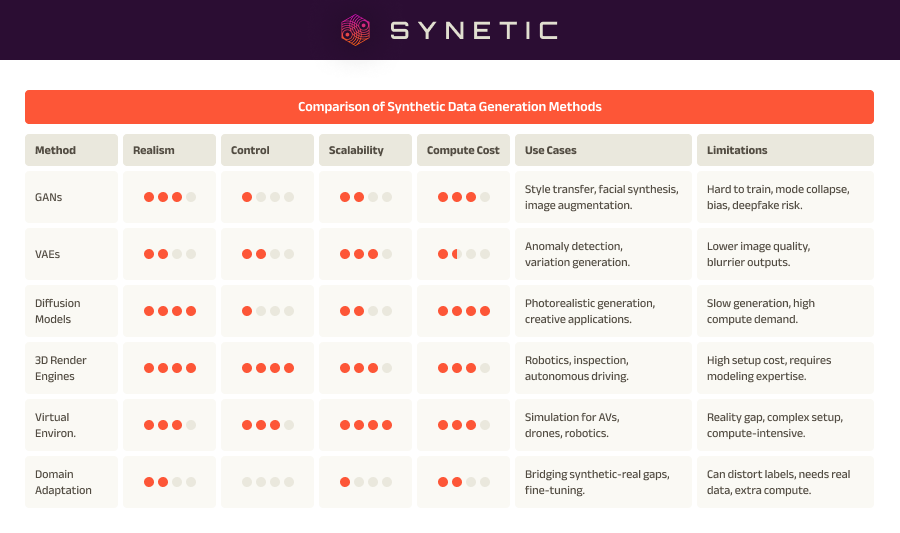

A comparison of synthetic data generation methods as they apply to different use cases.

How Synetic Frames Their Contribution

- A physics-based, multi-modal synthetic data platform

- Photorealistic rendering with accurate lighting, materials, and sensor models

- Support for RGB, depth, thermal, LiDAR, radar, and aligned labels [4]

- Built-in support for edge cases and rare events you can dial up or down

- A validation story, not just a generator

- The orchard benchmark is independently reviewed and reproduced by USC and uses 100% real-world validation data.

- They’re explicitly inviting companies in other sectors to run similar “synthetic-vs-real” tests against their own validation sets.

- A philosophy: synthetic as foundation, not augmentation

- In a separate whitepaper (“Breaking the Bottleneck: Synthetic Data as the New Foundation for Vision AI”), they argue that task-specific synthetic pipelines should be the default way to train high-performance vision models, with real data used sparingly and strategically.

You don’t have to agree with every part of that stance—but the orchard results make it hard to dismiss the idea outright.

If You’re Building a Vision System Today…

Three concrete questions this work suggests you should ask yourself:

- Could a synthetic-first pipeline cover my edge cases better than my current real dataset?

If your answer is “yes, but building the simulator feels daunting,” that’s a signal that simulation might be the right bottleneck to work on. - Am I treating my hand-labeled dataset as a gold standard when it’s actually messy and narrow?

It might be more accurate to treat it as a noisy measurement of reality and use it primarily for validation and sanity checks. - Is “just fine-tune on a bit of real data” actually helping—or quietly hurting—generalization?

It’s worth measuring performance not just on your “favorite” validation set, but on out-of-distribution data and at the low-confidence, low-IoU operating points you’ll actually use in production.

The apple-orchard benchmark doesn’t answer every question about synthetic data. But it’s a strong, concrete datapoint that training only on synthetic data, validated on real, can beat carefully collected real-only training—even in a messy, outdoor, real-world environment.

For many edge AI teams, that’s enough reason to at least run the experiment.

Note: All numerical improvements quoted here (mAP and recall deltas) are taken directly from Synetic’s Better Than Real whitepaper and associated benchmark tables.

Sources and Further Reading

Synetic & USC

- Better Than Real: Synthetic Apple Detection for Orchards – Synetic AI & University of South Carolina whitepaper (Nov 2025).

- Synetic.ai

- Breaking the Bottleneck: Synthetic Data as the New Foundation for Vision AI – Synetic AI whitepaper, July 2025.

- Synetic AI and University of South Carolina Announce Breakthrough Study: Fully Synthetic Data Outperforms Real by 34% – FIRA USA partner press release.

Broader context on synthetic data for vision

- Material Classification in the Wild: Do Synthesized Training Data Generalise Better than Real-World Training Data? – University of Essex, University of Birmingham, University of Bonn.

- PhytoSynth: Leveraging Multi-modal Generative Models for Crop Disease Data Generation with Novel Benchmarking and Prompt Engineering Approach – University of Florida Gulf Coast Research and Education Center, University of Florida Citrus Research and Education Center.

Footnotes

1 – Those recall and precision numbers—including the 22.14% recall lift—are reported at conf = 0.1 and IoU = 0.3, which the authors argue better reflects real deployment trade-offs than the usual 0.5/0.5 benchmark

2 – For this benchmark they trained on RGB images with synthetic 2D bounding boxes, but the same rendering pipeline is capable of emitting segmentation masks, depth, and 3D pose as needed for other tasks.

3 – In their published feature-space analysis of the same apple detection task, Synetic and the USC team fed both real and synthetic images through a YOLO model, projected the embeddings with PCA/t-SNE/UMAP, and reported complete overlap—no separate clusters for real vs synthetic. They summarize this as ‘zero statistical difference’ between synthetic and real feature representations.

4 – Beyond this apple benchmark—which uses RGB imagery only—Synetic’s platform supports multi-modal data (RGB, depth, thermal, LiDAR, radar) with perfectly aligned labels and sensor metadata