This article was originally published at 3LC’s website. It is reprinted here with the permission of 3LC.

Introduction

There’s been a lot of excitement lately around how foundation models (such as CLIP, SAM, Grounding DINO, etc.) can come close to human-level performance when labeling common objects, saving a ton of labeling effort and cost. It’s impressive progress. However, it raises an important question: should human performance be used as the ceiling? And what about the tricky cases (which are the most real industry cases), those domain-specific objects that not only require a subject matter expert to recognize, but also to reliably distinguish between visually similar classes that would be difficult for non-experts to tell apart?

In many computer vision tasks, human labelers are the de facto gold standard. But human accuracy itself – not just the time or cost of annotation – often becomes the performance bottleneck. Even subject matter experts introduce inconsistency and noise that can limit model performance.

Meanwhile, in specialized domains like infrastructure inspection, agriculture, or manufacturing, foundation models typically haven’t seen many relevant examples during pretraining. As a result, zero-shot or few-shot labeling approaches simply don’t hold up. They lack the domain knowledge required to produce reliable labels out of the box, even with a small number of fine-tuning examples.

In this article, we’ll walk through a practical case study showing how a light-touch human-in-the-loop, semi-automated labeling process can outperform both manual labeling and fully automated approaches, achieving a 40x speedup and cost reduction in the labeling process, while generating better-than-human-labels on a hard-to-label use case. This also saves costly subject matter experts from spending time on repetitive, obvious cases, so they can focus on the more difficult cases, exactly where their judgment really matters.

Partnership with eSmart Systems and Lambda

3LC.AI partnered with eSmart Systems, a global leader in AI-enabled power grid inspections, to ground this case study in a real production scenario. eSmart’s Grid Vision® platform is used by over 70 utilities worldwide to detect defects in millions of overhead line images. Their expertise and one of their many production models, a YOLOv5x6 model – trained on manually labeled bird nest data – provided the perfect benchmark to test our new workflow.

We also collaborated with Lambda, who generously supports us with GPU credits for our on-going research. Their purpose-built infrastructure for deep learning enabled us to efficiently run the iterative training cycles needed for this experiment.

These partnerships made it possible to rigorously compare the traditional, expert-labeled pipeline with a novel human-in-the-loop approach, using the same model architecture and dataset.

Ready-to-run scripts for Lambda, with 3LC and all code to reproduce this workflow, will soon be available here.

The Challenge with Pure Zero-Shot and Few-Shot Approaches

Recent work has demonstrated that foundation models can generate labels that achieve nearly human-level performance in zero-shot and few-shot settings for common objects. However, these approaches have several critical limitations:

- Specialized Domain Failure: Foundation models and zero/few-shot approaches perform well on common objects like cars or people – but fail in specialized domains where they’ve seen few or no examples during pretraining. These are precisely the cases where accurate labeling and domain expertise matter the most

- Human Accuracy Bottleneck: Aiming for human-level accuracy accepts human labeling errors and inconsistencies as the performance ceiling, but human accuracy is often the primary factor limiting model performance, not annotation speed or cost

- Lack of Nuanced Quality Control: Fully automatic labeling with a fixed confidence threshold is a blunt instrument. It often misses edge cases and subtle errors that require human judgment, especially in complex domains. Without a feedback loop, the auto-labeling process will silently introduce mistakes that degrade the dataset’s quality

The Domain Challenge

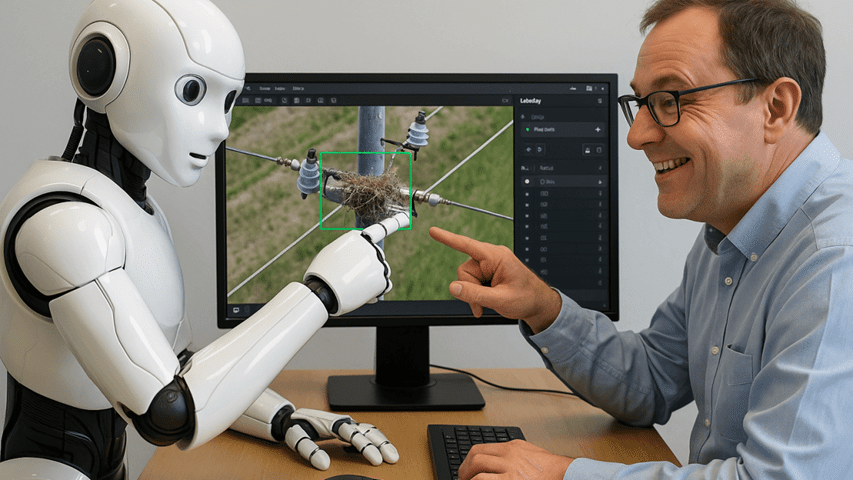

Our case study focuses on a real-world, high-stakes computer vision task: detecting bird nests in high-resolution drone footage of power grid lines – a critical infrastructure monitoring application, where accuracy directly impacts safety and maintenance decisions.

This task has already been tackled using a conventional approach: eSmart Systems manually labeled the dataset, using internal subject matter experts and external labelers, and trained a production YOLOv5x6 model on that data. This forms the baseline – the “traditional way” – against which we evaluate the labels created with our new, iterative workflow.

The domain exemplifies where zero- and few-shot methods consistently fail:

- Highly Specialized Objects: The variety of bird nests in power grid infrastructure are virtually absent from foundation model training data

- Complex Visual Context: Power lines, insulators, and vegetation create visually challenging backgrounds

- Varied Appearances: Nests vary significantly in size, material, and placement, requiring expert domain knowledge

- Human Labeling Inconsistencies: Even in this high-quality, production-grade dataset’s labels, we observed variability in bounding box tightness – some nests included surrounding branches or clutter, others were cropped too narrowly. This inconsistency introduces noise and impairs model learning

This project is a direct comparison: the same dataset, the same detection task, the same YOLOv5x6 model architecture – but two different labeling strategies. One is fully manual and already deployed in production, while the other leverages 3LC and Grounding DINO in a novel, light-touch human-in-the-loop workflow.

The goal: To test whether an iterative, human-in-the-loop labeling workflow – requiring less SME effort – could produce higher-quality labels than the manually annotated production dataset, and whether those labels would in turn support a more accurate model when trained under identical conditions. This is exactly the kind of complex, domain-specific task where zero/few-shot approaches fall short, and where a better workflow can raise the ceiling beyond human limitations.

3LC’s Human-in-the-Loop Workflow

Instead of pure zero-shot or few-shot labeling, we developed an iterative semi-automated approach using 3LC (a data-centric AI platform), a subject matter expert who observes and decides, and fine-tuning of a Vision Language Model (Grounding DINO) for each iteration.

Phase 1: Initial Human Seed Set

- Start from scratch: We began with an entirely unlabeled dataset of 4960 drone images.

- Small expert labeling round: Using 3LC’s interface, a subject matter expert quickly labeled 100 images (labeling bird nests). These 100 serve as the initial “seed” training set. This took around 15 minutes in the 3LC interface

- Weighted training data: In 3LC, we set the labeled images to weight = 1 (include in training) and all other images to weight = 0 (exclude from training, but still available for prediction and tracking). This way, the model trains only on the expert-labeled seed images for the first iteration, while still making predictions on all images

- Initial model fine-tuning: We fine-tuned Grounding DINO on this 100-image seed set. The training script was integrated with 3LC’s API, so it could automatically pull the latest dataset revision and log per-sample metrics and predictions. After this step, we had a rough model that started to recognize bird nests (though not perfectly)

Starting with a fully unlabeled dataset, labelling 100 images in random order for the initial seed set finetuning

Phase 2: Iterative Quality-Controlled Label Expansion

The key innovation was our iterative quality-control mechanism:

- SME confidence adjustment: After training on the 100 seed images, the model produced predictions (bounding boxes with confidence scores) on all the images, including the unlabeled ones. We opened the training run with its captured metrics in the 3LC dashboard and reviewed the predictions that had no overlapping ground truth (mostly on unlabeled images) in random order. The SME reviewed each prediction and decided if it was correct. We aimed to find 50 correct predictions in a row. If an incorrect prediction popped up before reaching 50, the expert would raise the confidence filter slider to just above that faulty prediction’s confidence, and then we’d restart the counting process. This method ensured we weren’t cherry-picking easy images – we were truly testing if the model could sustain a low error rate at a given confidence level. This step is a seamless and quick process in 3LC, where the SME functions as a validator and quickly browses through the 50 predictions, and it never took more than 5-10 minutes for any iteration.

- Confidence-based acceptance: Once we identified a confidence level at which the model could make ~50 correct predictions in a row, we could now add all the currently filtered-in predictions as new labels in the 3LC dashboard. We marked those newly labeled images with weight = 1 (so the next training round would include them).

- Retraining with new revision: We fine-tuned the model again using the expanded training set – the original 100 seed labels plus the newly added high-confidence labels. With 3LC’s dataset versioning and PyTorch integration, the script automatically pulls the latest revision, eliminating manual file handling. We simply re-ran the training script, and the model trained on the updated data.

- Repeat: We repeated the train → find confidence → add labels workflow for multiple iterations. For each cycle, the model improved slightly, and we could add more of its predictions (always at a ~2% error rate*). We continued until it was impossible to find 50 consecutive correct predictions, no matter how high we set the confidence threshold. At iteration 7, with ~300 images left, we hit the limit. At that stage, the model’s remaining predictions on unlabeled data were simply too unreliable to trust without human review. It also indicates that those remaining 300 images are hard samples.

After first finetuning run, the SME find the confidence threshold needed for finding 50 random predictions in a row that is correct. This added 1098 new Bounding Boxes in this iteration.

(*Why 50 in a row? Hitting 50 correct predictions consecutively gave us high statistical confidence that the model’s error rate on the predictions above that confidence was at most ~2%. If we wanted to be even stricter, we could have used 100 in a row for a ~1% error guarantee, but 50 was a practical balance for this project. That said, with larger datasets – say 50,000 images – this number should probably be higher to ensure the guarantee holds with stronger statistical confidence.)

Phase 3: Final Manual Review

After 7 iterations of adding labels and retraining, the vast majority of the dataset was labeled. We reached a point where about 300 images (out of ~4,960 total) were still unlabeled because their predictions never met our ~98% accuracy threshold / 50 correct in a row, at any confidence level. For this final subset, we switched back to manual mode: the SME rapidly went through these 300 images using 3LC’s interface, verifying or correcting the model’s last predictions. This final manual step took about 30 minutes of work.

It’s worth noting that many of these remaining images had model predictions with quite high confidence (some as high as 0.97) – yet a number of them were false positives. If we had allowed the model to auto-label everything without this last human check, those errors would have polluted the dataset. The same would have happened if we had added all predictions at a fixed confidence level after one training iteration. This underscores the value of human-in-the-loop validation, as it caught the final few mistakes and ensured the label error rate stayed around 2% overall.

Results: Exceeding Human Performance on Hard-to-Label Data

The results demonstrate the power of human-machine collaboration on challenging, domain-specific labeling tasks where zero-shot or few-shot methods fail entirely. We were able to improve model accuracy compared to the high-quality dataset labeled by a eSmart Systems. And, we only used 2 human hours, compared to 80 human hours for the manually labeled dataset, removing a lot of repetitive and costly SME work.

To verify the performance, we trained YOLOv5x6 – the model architecture already used in production by eSmart Systems – on both the originally labeled data and the data that was labeled using 3LC’s iterative workflow.

Model Performance Metrics:

- Detection Accuracy (mAP) – On the evaluation set, the model trained on traditional human annotations achieved an mAP@50 of 0.8886, and a stricter mAP@50-95 of 0.4205. By contrast, the model trained on the semi-automatically labeled data hit an mAP@50 of 0.8896 and mAP@50-95 of 0.5595. That’s essentially the same easy-case accuracy, but a 33% boost in the harder, overall IoU range metric (0.5595 vs 0.4205). In other words, the model was significantly better at precise localization when using the cleaner, more consistent labels from our workflow.

Key Improvements:

- 33% increase in mAP50-95 (the more stringent metric)

- Superior bounding box precision: Machine-assisted labels were consistently more “snug” than human labels

- Consistent quality: Max 2% error rate maintenance throughout the process

- Overcame human accuracy bottleneck: Achieved better-than-human performance on the production model on a very challenging labeling task

Efficiency Gains

- Human Time: Total human effort was reduced from 80 hours (reported by eSmart Systems for their labeling process) to just 2 hours – a 40× speedup. Breakdown for the new workflow: ~15 minutes to label the initial 100 images, several 5–10 minute confidence-finding sessions across 7 iterations, and ~30 minutes for the final review of 300 remaining images. Over 4,600 images were labeled by the model rather than a person.

- Cost Range in Different Labeling Scenarios: In eSmart’s case, a mix of different resources was used, including internal subject matter experts (SMEs). Combined cost was about $3,200 total – where our method still delivers a 16× cost saving. In many industries such as defense, energy, or medical imaging, SMEs often perform all the labeling. At SME rates of $100–$150/hour (agriculture/energy) or $150–$250/hour (medical), the same 80 hours would cost $8,000–$16,000. In those scenarios, our approach yields both the same 40× speedup and up to 40× cost reduction.

- Compute Time: 20 hours on a single Lambda A100 node, costing about $30.

- Iterations & Output: 7 iterative cycles of model training and label expansion produced a final dataset of 4,960 high-quality labeled images ready for production training – all with minimal but highly important and targeted SME input.

Conclusion

This case study represents a practical step forward in tackling the human accuracy bottleneck in labeling. By combining targeted subject matter expertise with model automation, we achieved labeling quality exceeding the subject matter expert efforts alone on a task where foundational model auto-labeling would also fail. Furthermore, we did it in a fraction of the time that pure manual labeling would have taken, reducing the amount of SME work time by a factor of 40.

In most computer vision domains, zero-shot and few-shot approaches are often not viable, and relying solely on human labels is slow, expensive, and prone to inconsistencies. Our results show that a well-designed human-in-the-loop workflow (powered by 3LC’s data-centric platform and iterative model fine-tuning) can yield superior outcomes to either approach alone. We were able to rapidly generate a large volume of accurate and consistent annotations for a previously hard-to-label problem, enabling a better model in the end.

One key insight is that subject matter experts remain crucial for quality control – their judgment is what guides the model and curates the labels. However, we don’t have to accept the limitations of manual labeling accuracy. By using the machine to handle the obvious cases and produce consistent labels, and the human to validate the model’s output and edge cases, the overall system can surpass what either could do alone, in a fraction of the time.

As we continue to develop AI workflows, the focus shouldn’t be on achieving human-level performance or replacing human expertise entirely. Instead, we should create collaborative workflows that overcome human accuracy limitations while leveraging the unique strengths of both humans and machines.

Thanks to eSmart Systems and Lambda for this collaboration!

Other notes:

The initial 100 SME labels were replaced with Grounding DINO’s predictions in the 3LC Dashboard, as these were more consistent than the labels created in the initial phase. In the SME-created evaluation set used for evaluation, we also replaced labels that had a high IoU overlap with Grounding DINO’s predictions, ensuring those labels were equally consistent.

Novelty Statement:

While human-in-the-loop labeling and active learning are established concepts, prior work has largely focused on matching human-level annotation quality or reducing labeling time on generic datasets. This study is the first to demonstrate, in a real-world production setting that it is possible to systematically surpass the quality of expert-labeled production data in a specialized domain. We introduce a reproducible, statistically grounded “50-correct-in-a-row” acceptance criterion that maintains a ≤2% label error rate while enabling iterative model-driven label expansion, where using an SME for each iteration is key. Applied to a high-stakes, domain-specific task (bird nest detection on power grid lines), this approach achieved a 33% improvement in mAP50–95 over the expert-labeled production baseline, with a 40× reduction in subject matter expert time. To our knowledge, this is the first documented case where an iterative SME-guided auto-labeling workflow has both exceeded human label quality and substantially reduced labeling cost in a deployed industrial computer vision pipeline.

Original article written by Paul Endresen and posted on LinkedIn on August 13, 2025: Breaking the Human Accuracy Barrier in Computer Vision Labeling | LinkedIn